I Know You Have a Mental Illness. But I Am Only Human

Mental Health Awareness Week includes the health of those who care for someone with a mental illness.

For the past five years, in family support groups and online discussion boards, I have heard the following words from those with depressed partners and spouses.

I get it. I do understand.

Each day is a struggle for you to get out of bed, let alone wash the dishes or do the laundry. It’s been two years since you cooked a meal or drove the kids to school or danced with me or held me during the night.

You are consumed by depression.

You hate feeling this way. You hate being stuck on the couch. You hate not going outside. You hate how none of your treatments have helped. You hate how much weight you’ve gained from the meds, how no one calls you, how shitty you feel, how much guilt you feel for how little you can give to our marriage.

You are smothered by the central paradox: To get better you must get out of bed, but to get out bed you must get better.

You didn’t ask to be depressed. It’s not your fault.

The central paradox: To get better you must get out of bed. But to get out of bed you must get better.

So I do everything. I help the kids with their homework. I take them to soccer. I sign the permission slips and I pay the bills. I cook the meals and clean up the kitchen and take out the garbage. I drive you to your appointments. I work and I work and I encourage you and I pray for you and never judge you and read about new therapies. I battle the stigma and cling to the hope that someday you will get better because without hope you and I and our family are doomed.

But, honey, I am only human. I promised to love you through sickness and in health, yet your depression blankets our home like a nimbus cloud. I get resentful. I whine and I sulk and wonder if I am enabling you. I withdraw emotionally. I fantasize. I drink. I drive too fast. I drown in self-pity and guilt and teeter between rage and despair. I grieve ambiguously because I strive to see you as a person rather than an illness, yet you say you no longer know who you really are. So how am I to know?

My therapist tells me to go easy on myself. Take care of yourself, he says. Live life one day at a time. So I play poker and hike and fish for trout and watch too much TV. But my hair is thinning and my loins are aching and I get angry at God and the universe. What does it mean to live one day at a time when I dread I will come home and find you have taken your life? What does it mean to be thirty years old and worry whether by the time I am sixty my life will have passed me by? What does it mean to be sixty and wonder where the time has gone and if this is the end of the road?

I am sorry.

I love you. We are in this together. I will never give up hope, at least for now.

Like you, I am only human.

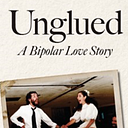

My wife Leah, who has bipolar disorder, and I are among the fortunate who can offer hope to those battling a mood disorder and to their loved ones. You can read about how both our marriage and I became nearly unglued in my memoir, Unglued: A Bipolar Love Story (Boyle & Dalton, 2020).